Sandra Cisneros' Woman Hollering Creek is a story about love/passion and control. The text includes excerpts of Cleofilas' narration, third person narration, and portions of other women's gossip-filled conversations about Cleofilas. In the opening paragraph of the text, Cleofilas is described as Juan Pedro's bride and Don Serafin's daughter; her status in society is dependent on her constricting and culturally assigned gender role. Cleofilas' passivity is wrapped up both in this gender role and in her preoccupation with idealized love (largely from the various telenovelas, or soap operas, that she watches): "Somehow one ought to live one's life like that, don't you think? You or no one. Because to suffer for love is good. The pain is all sweet somehow. In the end" (p. 3165). Cleofilas discovers that in the reality of a marriage plagued by the never-ending cycle of domestic abuse, suffering for love is not quite as sweet as she had originally thought it to be.

I feel sympathy for Cleofilas and find myself wishing that she would leave her husband. The titular Woman Hollering creek shows Cleofilas' emotional journey throughout the text; Cleofilas, trapped in an abusive relationship, no longer has the opportunity to watch soap operas as frequently as she once had, and the romanticism that once thrived on the drama and relationships of this idealized world becomes focused on the mystery and beauty of the creek. Juan Pedro "doesn't care at all for music or telenovelas or romance or roses or the moon floating pearly over the arroyo, or through the bedroom window for that matter, shut the blinds and go back to sleep, this man, this father, this rival, this keeper, this lord, this master, this husband till kingdom come" (p. 3168).

Cleofilas' changing perception of the creek throughout the text is evidence of her gradually changing perspective. When she "drove over the bridge the first time as a newlywed... Juan Pedro has pointed it out [and called the creek] La Gritona ["the loud"]... and she had laughed. Such a funny name for a creek so pretty and full of happily ever after" (p. 3166). As Cleofilas realizes the stark reality of her isolation, she finds solace in the creek and it becomes a place of refuge for her; she explains that in the town in which she lives there is "... nothing, nothing, nothing of interest. Nothing one could walk to, at any rate. Because the towns here are built so that you have to depend on husbands. Or you stay home... There is no place to go. Unless one counts the neighbor ladies... or the creek" (p. 3168). Cleofilas describes the creek as "a good-size alive thing, a thing with a voice all its own, all day and all night calling in its high, silver voice" (p. 3169).

When Felice is driving Cleofilas and her son out of town, leaving Juan Pedro behind, Cisneros uses the creek to show the potential of Cleofilas' imminent freedom and the potential for Cleofilas to take control of her own life for the first time: "But when they drove across the arroyo, the driver opened her mouth and let out a yell as loud as any mariachi" (p. 3171). Felice explains, "Every time I drive across that bridge I do that. Because of the name, you know. Woman hollering... Did you ever notice, Felice continued, how nothing around here is named after a woman? Really.... That's why I like the name of that arroyo. Makes you want to holler like Tarzan, right?" (p. 3171). Cleofilas' amazement at "everything about this woman" (p. 3171), and the independence expressed in her hollering, seems to awaken a desire for independence. In the closing lines of the text, Cisneros notes that "then Felice began laughing again, but it wasn't Felice laughing. It was gurgling out of her own throat, a long ribbon of laughter, like water" (p. 3171). In this way, Cisneros uses the creek to express feminine power and the freedom to have control over one's own life. The end of the story is open-ended: what happens to Cleofilas? Did she return to her brothers and father in Mexico? Did Juan Pedro find her and drag her back to their home? Or did she, in her newfound freedom, establish her own life elsewhere, on her terms? I hope so.

ellen from down under

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Long Day's Journey into Night

Eugene O’Neill’s play Long Day’s Journey into Night is a tragic story about family dynamics, communication, and conflict. The play is set in August of 1912 in the summer home of the Tyrone family. The entire play explores the events of a single day in the life of this family and paints a grim but realistic picture of their struggles and family relationships. Simultaneously, Long Day’s Journey into Night presents the Tyrones’ “journey through life toward death” (p. 1609); it becomes increasingly obvious throughout the play that this day is one of many similar days experienced by the Tyrones.

The play is largely autobiographical. The struggles of O’Neill’s characters mirror his personal life in many ways, and the character of Mary is based loosely on his mother, who was addicted to morphine. Alcoholism also plagued the O’Neill family, and the ramifications of this are reflected in Long Day’s Journey into Night. The play is a frank portrayal of the issues that can overrun family relationships and the delicate family dynamics that develop over time, often as a result of hardship. O’Neill writes with honesty about unmet expectations, unfulfilled dreams, and relationships that throughout the course of life have become bogged down in a mire of disappointment and disrespect. The Tyrone family is essentially living in their past- bitterness and a lack of forgiveness prevents each family member from harnessing their potential and sharing a more harmonious life. The tangibly raw emotion expressed by O’Neill’s characters is testament to his perfection of his craft.

O’Neill’s meticulous attention to detail is obvious in his lengthy descriptions about each scene (the italicized portions). In my opinion this suggests that the play is intended to be both performed and read, especially as many of the specific details (a list of the books that appear on the bookshelf, for example) would never be seen by an audience. A degree of intertextuality is evident within the play as O’Neill has his characters quote lines of Shakespeare (which is of course fitting, as several family members are actors). Structurally, Long Day’s Journey into Night is a series of emotionally intense encounters that feature different combinations of family members until every potential combination is exhausted. This technique allows O’Neill to explore relationships between individual characters and evaluate how these relationships contribute to the greater family dynamic. The relationship between Tyrone and Jamie, for example, is particularly difficult, and the underlying issues that continually fracture their bond are revealed in greater clarity in the scene in which they are alone together.

O’Neill is a master of character; each scene reveals different elements of the characters’ personalities and provides the audience with a deeper understanding of the characters’ lives and personas as the play progresses. The audience gradually finds out pieces of information about the family members, such as Edmund’s tuberculosis and Mary’s morphine addiction. This gradual revelation of facts heightens the play’s suspense and piques the audience’s interest. O’Neill’s depth of character development, coupled with his relatively unbiased presentation of family conflict, draws the audience into the script. Indeed, the dialogue of the play is so painfully genuine and wrought with such tangible emotion that O’Neill enables the audience to relate to issues that arise within the play on a deep level. In this way, Long Day’s Journey into Night transcends the time and place in which it was written and elevates to a higher plane- one in which struggles of communication, conflict, addiction, despair, unmet expectations, and difficult family relationships are understood on a universal level.

O'Neill, Eugene. “Long Day's Journey into Night.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Ed. Nina Baym. New York: Norton, 2007. 1607-85.

Tuesday, March 8, 2011

The Waste Land

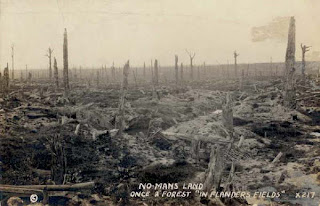

The Waste Land, by T.S. Eliot, was published in 1922 in Criterion, a British magazine, and in the American magazine Dial. It is a revolutionary poem, one that fundamentally changed preconceptions of “what poetry was and how it worked” (p. 1574). Its publication was a “cultural and literary event” (p. 1574) that captured the essence of post World War I life. The destruction and brutality of this ‘war to end all wars’ caused people to look inward and question the potential of humanity to inflict intolerable cruelty and wreak total destruction; poets, authors, and artists reflected this introspective concern in their creative mediums.

In my opinion, the beginning of the poem seems to describe the effects of the different seasons on the barren wasteland that exists after a war has ravaged the trees to stumps and churned the dirt to mud. Perhaps Eliot calls April “the cruelest month” in the opening line of the poem because the regeneration of new life and the growth of “lilacs out of the dead land” (line 2) stands in such stark contrast to the atrocities that had previously occurred there; in some way the encroaching seasons symbolized the waste of the soldiers’ lives (because the seasons keep cycling and the details of the war will eventually be forgotten). To me, these opening lines of the poem reflect the often-fragile relationship between remembering the past while looking to the future; this is particularly evident in Eliot’s lines “mixing / Memory and desire, stirring / Dull roots with spring rain” (lines 2-4).

The Waste Land is a puzzle-like poem in that Eliot interlaces copious literary and religious references within each stanza. It is written for an intellectual audience, and it is a complicated poem that critiques modern civilization. The text concisely explains The Waste Land’s structure and states that it “consists of five discontinuous segments, each composed of fragments incorporating multiple voices and characters, literary and historical allusions, vignettes of contemporary life, surrealistic images, myths, and legends” (p. 1575). The inclusion of all of these elements and the somewhat random nature of the poem give it a disjointed feel- the reader never knows quite where Eliot is or where he’s going next.

The pessimism of Eliot’s poem is evident throughout each vignette but is particularly obvious in the poem’s classical epigraph: “For once I myself saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a cage, and when the boys said to her, ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’ she replied, ‘I want to die.’” (p. 1587) To me, this symbolizes Eliot’s pessimistic attitude about modern civilization and his bleak view of the future, both of which seem to stem from the tragedy of World War I and the stark observation of humanity’s destructive potential. The poem is essentially a critique of the modern condition. While this observation may appear obtuse, it seems that the disjointed structure and essence of the poem may in itself allude to the lack of a unifying element in modern society. The decay of religious influence and tradition in mainstream modern culture, either through neglect or outright rejection, saw the influx of modernism and a pace of change (artistic, technological, and social) that had never been experienced before. Eliot’s poem laments the ‘shock of the new’ and the radical change and rejection of tradition brought on by a post war twentieth century, as well as the innocence of the past that suddenly seemed irrevocably changed. The Waste Land is a requiem for a simpler time.

Eliot, T.S. “The Waste Land.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Ed. Nina Baym. New York: Norton, 2007. 1574-98.

Monday, March 7, 2011

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock was written by T.S. Eliot and published in 1915. It is a dramatic monologue that is reminiscent of Freud’s “stream of consciousness” theory. The poem is distinctly modern, written with a high degree of intellectuality, and intended for educated readers. It seems to be a lament about Prufrock’s missed opportunities and neurotic insecurity. Eliot presents Prufrock as a hopelessly shy man who is incapable of forming relationships, or even talking, to women. This is evident in line 69 when Prufrock asks, “And how should I begin?” after an entire stanza of descriptions of women’s arms...

I’m not sure how I feel about this poem. I like how it rhymes, and I appreciate how Eliot uses repetition and a seemingly random rhyme scheme, but the larger purpose of the poem is lost on me (perhaps I’m just too tired to understand it?!)

Eliot repeats several lines throughout the poem:

- “In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo” (13-4 & 35-6)

- “And indeed there will be time” (23 & 37)

- “So how should I presume?” (54) … “And should I then presume?” (68)

- “For I have known them all already, known them all” (49) … “And I have known the eyes already, known them all” (55)

- “Should say: ‘That is not what I meant at all. / That is not it, at all.’” (97-8) … “That is not it at all, / That is not what I meant, at all” (109-10)

These lines seem to underscore Prufrock’s insecurity.

I find it ironic that throughout the poem Eliot presents Prufrock as an eloquent writer, and yet the purpose of the poem seems to be to explore his insecurity and inability to develop relationships. Prufrock is overly concerned with what other people think about him and he’s afraid to communicate with other people because they may judge him based on his appearance. Prufrock’s melancholy is clear throughout the poem.

Eliot’s inclusion of an epigraph, a short portion of Dante’s Inferno, provides some insight into the poet’s purpose. According to the text, the speaker openly confesses his shame in this epigraph because he doesn’t believe that Dante can report it because he can’t return to earth. This suggests that Prufrock’s honesty and articulateness (in writing) comes only as a result of introspection and in hindsight after a life-changing event. The paradox of the poem is that if Prufrock had pursued introspection and been able to identify and express the emotions that are present within the poem, he may have gained some confidence and negated the need for such a poem.

Ultimately, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock seems to be a poem about self-realization and self-actualization and the potential that every person has for introspection and insecurity. While Eliot obviously uses Prufrock’s character to communicate various observations about the human condition and thus give the poem some redeeming value, I am so aggravated by the degree to which Prufrock wallows in his own self-defeating stupor that I am perhaps unable to appreciate the poem for its intended purpose. Much of its meaning is decidedly, at this point, lost on me.

Monday, February 28, 2011

In a Station of the Metro

Wow. My first impression of Pound’s In a Station of the Metro was that it is… short (even shorter than Sandburg’s Fog)! It’s concise, and definitely an imagist poem: slimmed down, stripped bare, distilled to a simple, unembellished form. Despite, and yet perhaps thanks to its astounding brevity, Pound’s poem is surprisingly beautiful. It draws a unique metaphoric relationship between two otherwise unrelated images.

It makes me think of a dark street (train track, subway tunnel, etc.) stretching into the distance and the white faces of travelers in the foreground, some close, some further away, that stand out against the bleakness of their surroundings like beautiful “petals” against the bough of a tree. The use of the word “apparition” (and indeed the feeling and imagery that the poem evokes) gives the poem a wistful, ghostly, misty, and memory-like quality, as if the poet is recalling faces from his memory that stand out against the black expanse of his life (that stretches into the future like the branch of a tree into the wind, or a subway tunnel into the distance).

Pound’s haiku-style poem compresses an entire image into two lines. Its simplicity allows the reader to draw their own meaning from the images that it creates and the feeling that it evokes, with each interpretation of the poem influenced by the unique experiences of the reader.

I grew up in Australia and I am constantly shocked when I see a face in a crowd here that is the “spitting image” of someone from home, and not even anyone especially significant to my life… the mother of a girl I went to school with, my brother’s first grade teacher, a guy who pushed carts for a supermarket in my home town, etc. Especially during my first few years living here, these faces were like “petals” from my memory- apparitions of something familiar and known… that stood out against the “wet, black bough” that was the foreign and lonely place in which I found myself.

The juxtaposition of “petals” and “wet, black bough” is interesting because each element exudes a completely different vibe; petals are light, delicate, beautiful, and somewhat jovial, while “a wet, black bough” seems strong, cold, and harsh in comparison. Pound’s metaphor, while surprising, seems apt- bright and beautiful petals set against a wet, black bough are like familiar faces spotted in an alien crowd.

Chicago

Sandburg's Chicago made me think of Detroit because of this ad:

http://www.youtube.com/user/chrysler?bid=5079147&adid=233347236&pid=57249858&KWNM=detroit&KWID=150768528&channel=PS

http://www.youtube.com/user/chrysler?bid=5079147&adid=233347236&pid=57249858&KWNM=detroit&KWID=150768528&channel=PS

Saturday, February 19, 2011

I'm finally getting somewhere...

I am not a blogger. In fact, the idea of potentially having to "write" in html blog-speak is rather daunting. At least I've finally got the actual blog established, though... here goes! Watch this space!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)